Identifying as Chicano is a choice, and one that has

produced a sense of homeland, despite my not being of Mexican descent. I am the

son of Honduran and Ecuadorian parents. What that exactly means? I honestly

have no idea. I love pupusas and have learned about a regional Honduran

context, local Garifuna and Maya histories, and not too much more from my

Ecuadorian side except that we run off of Spanish bloodlines and a Nacza

lineage—mind you this is powerful in itself, but I just didn’t feel connected.

Not much more to it, although there could be I’m sure if I took the time. But I

found something else that spoke to my struggle, that adopted me and rooted me

in something, in somewhere. I am Chicano…

However according to mainstream Chican@ discourse being born

of Centro and Sur American parents and raised under Caribbean urban influences

in the East coast, really doesn’t qualify entry to the Southwestern borderland

identity—I got to bleed Mexico in some fashion or another apparently. Whenever asked

what I am or what I identify as, I mention my parents then that I identify as

Chicano, but I’m scrutinized carefully and then told I can’t because I’m not a

Mexican born and raised here. Whatever…fragmented, I guess is the best way to

describe myself.

I came from one of the most diverse cities in the states,

yet I felt that I could not classify myself. The term Latino proved to be

hollow in defining who I was. I did not speak Spanish well, and Latinos from

Latin America all called me Gringo. In other words, I was rejected. I could not

claim their identity, nor their space, because I was not of them. Gringos/White

people did not claim me either. White people would ask me where I was from, I

stated NY but then they responded jokingly, “No, like where are you really

from.” As if who I was had to be construed as foreign. Why did I have to be a

stranger to this country?

I came from one of the most diverse cities in the states,

yet I felt that I could not classify myself. The term Latino proved to be

hollow in defining who I was. I did not speak Spanish well, and Latinos from

Latin America all called me Gringo. In other words, I was rejected. I could not

claim their identity, nor their space, because I was not of them. Gringos/White

people did not claim me either. White people would ask me where I was from, I

stated NY but then they responded jokingly, “No, like where are you really

from.” As if who I was had to be construed as foreign. Why did I have to be a

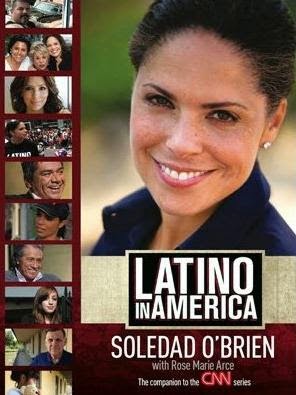

stranger to this country? I came in contact with the term Chicano in Utah through a

book by Soledad O’Brian. Soledad described her experience as a journey webbed in

social identities and opposing messages. She needed a label, but was surrounded

by categories that had vied for her attention and fought for ownership. For the

first time ever, I felt I had read something that spoke to what I was feeling,

to what I felt haunted me my whole life—I believe Soledad had one hell of a

journey too because her parents were Irish and Afro Cuban.

I came in contact with the term Chicano in Utah through a

book by Soledad O’Brian. Soledad described her experience as a journey webbed in

social identities and opposing messages. She needed a label, but was surrounded

by categories that had vied for her attention and fought for ownership. For the

first time ever, I felt I had read something that spoke to what I was feeling,

to what I felt haunted me my whole life—I believe Soledad had one hell of a

journey too because her parents were Irish and Afro Cuban.

After Soledad I pick up on the term Chicano when I met other

Latinos—specifically Mexican-American—who were not from Mexico but purposely

re-identified themselves as from neither here nor there. I was amazed. This is

what I felt, and they called themselves Chicanos. They seemed at peace with

themselves, regardless of how often they defended their titles against Latin

Americans. I began to search myself. Chicano authors like Corky Gonzalez,

Sandra Cisneros and Rudolfo Anaya began to fill the void that broke me,

fragmented me, and in their words I felt whole. In their words I discovered the

middle ground, the separation of worlds and merging of perspectives, of

occupying a mental state that was only intensified by a real-time geography

experience.

I finally picked up Anzaldua—a Chican@ must-read—and never

had someone’s words stimulate both body and spirit. Her writing was beckoning

me to come home. Where? That was the thing, it wasn’t a real place I had to

choose from; it was a space I could dictate and define according to my terms.

The Borderlands. Anzaldua touched my heart and fulfilled me: “Until I am free to write bilingually and to switch

codes without having always to translate, while I still have to speak English

or Spanish when I would rather speak Spanglish, and as long as I have to

accommodate the English speakers rather than having them accommodate me, my

tongue will be illegitimate. I will no longer be made to feel ashamed of

existing. I will have my voice: Indian, Spanish, white. I will have my

serpent's tongue - my woman's voice, my sexual voice, my poet's voice. I will

overcome the tradition of silence…I want the freedom to carve and chisel my own

face, to staunch the bleeding with ashes, to fashion my own gods out of my

entrails...”

In mentioning Anzaluda, I have to be honest in that her

literature very much represents the intersecting nuances of gender and

sexuality at the same time as race. To withhold that information would fall on

account of my privilege as male, and heterosexuality as a normative feature of

society. Yet these additive features to identity—although I could not relate to

and rightfully so—taught me so much more of the intricacy within the social

constructs of self, and the power in disrupting categories by naming your own

spaces. At the time, this was my gospel.

So I decided that I identify as Chicano. Why not? If race

and identity is socially constructed, who are you to tell me where I belong and

to who? The difficulty now is helping other Chicanos—specically

Mexican-American Chicanos—come to terms with the fact that I too can identify

as Chicano. Sadly, most Latinos and Chicanos have a very misunderstood and

lacking conception of the term itself. Welcome to colonial imperialism 101.

Historically Chicano derives from the transculturation of

Spanish and Indigenous language in Central Mexico originating in the conquest.

One version contests that the origin of the term grew from the evolution of

language in which Mestizos or Indigenous Mexicans came to be known as

considering the real pronunciation of the Azteca people—the Mexica (the X being

pronounced as a “sh” or “ch”). So one argument is the resulting cocktail of

language that is used as a derogatory term to affiliate individuals who could

not exactly adopt both worlds (Indigenous or European) or those who lived in

the Northern lands till Mexico and the Western half of the United States were

coerced as an imperialist strategy. This is one version and there are many.

But as we soak in the literature of the Chicano movement

from the Civil Rights era and look at the anti-colonial aspect of what it’s

formed into—a very anti-assimilationist project—we see resistance as a

prevailing theme for what Chican@ truly signifies. Yes it might be a creative

exchange of Spanish and Indigenous languages, but it is also the

re-appropriation of resistance for a group who really had/has no home. It

demands self-determination and representation. It seeks voice. That’s why the

term speaks to me.

But as we soak in the literature of the Chicano movement

from the Civil Rights era and look at the anti-colonial aspect of what it’s

formed into—a very anti-assimilationist project—we see resistance as a

prevailing theme for what Chican@ truly signifies. Yes it might be a creative

exchange of Spanish and Indigenous languages, but it is also the

re-appropriation of resistance for a group who really had/has no home. It

demands self-determination and representation. It seeks voice. That’s why the

term speaks to me.

But what about the African or Black experience of Latin America? Does

my identity not encompass that portion? Culturally? Racially? Yes. It

does.

Honduras and Ecuador are home to Afro-Latino demographics

and to deny them as part of my reality would be disappearing them from a larger

framework—this is how an entire people fade; their stories are never told. Neither is this process new. Just like the

Indigenous struggle of identity and representation, the members of the African

diaspora in Latin America face an equally oppressive challenge. No one wants to identify as Black…Colonialism

part II—Mexico also had 4X as many African slaves delivered to their shores

than the United States, FOUR TIMES as many, which suggests Mexico is just as

much Black as it is Indigenous or European (you see, entire histories

disappear)…

|

| Mad love and respect to Juan Ernesto (Tan shirt on the right) who passed away. You're still in our memories hermano...Rest in power... |

Nevertheless, as I seek to untangle and not fragment, but

keep whole, I come to realize that there is true danger in the complexity that

I’ve arrived at. Rose Clemente critiques the neutrality of the 1/3 argument,

which is so contagious in the Caribbean—I am 1/3 Indigenous, 1/3 African, and

1/3 European. Contradictory to its own nature, hybridity results in the

dominance and expression of ones identity, the colonizers’. This hides the

racialized component of systemic oppression in one body. They will not see

three in one, but only one; and it will be the most European, the most Western,

the most White, and the most male. Politically this is a disadvantage.

Therefore, I identify as Chicano as a politically empowered

front, but I take it a step further than that. I do what Junot Diaz does, I

carry from the Caribbean and I introduce my other hidden selves by challenge

through creation. I add my home geography because place and space are critical

in this development, and I contribute with a contextualized Black experience of

the Afro Caribbean. In other words, I arrive at my own etymology, my own

conception of the borderlands and ocean gulfs: I am Chicano Newyorquino.

So let me make myself whole again, let me reintroduce the

assorted voices into my one body, and by extension the knowledge I wish to

share with my son one day. I’ve created the Chicano Newyorquino to withdraw

from a Western categorization and deliver an alternative, something that speaks

to my racial politics of adopting Atzlan as homeland, of resistance as dance

and Santeria, of occupying, of disrupting, of transcending, of loving because

my Brooklyn experience is all of this!…BUT…I say this with the understanding

that a radical racial politics must also arrive for Centro Americano identities

and Sur Americano bodies, LIKE ME! We can’t leave these folks hanging and

expect that our alternative discourses naturally fit them or just plain old

exclude them; yet they will have to define the parameters of their own

philosophy—no one else should. It will be an in-depth and long project of race

and decolonization. It begins ,and should be encouraged—not stifled—by all of

us. In fact, it is beginning though with the heavy entrance of Central American

youth into the United States from the frontera. People are beginning to realize

that countries like Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras actually exist!

So let me make myself whole again, let me reintroduce the

assorted voices into my one body, and by extension the knowledge I wish to

share with my son one day. I’ve created the Chicano Newyorquino to withdraw

from a Western categorization and deliver an alternative, something that speaks

to my racial politics of adopting Atzlan as homeland, of resistance as dance

and Santeria, of occupying, of disrupting, of transcending, of loving because

my Brooklyn experience is all of this!…BUT…I say this with the understanding

that a radical racial politics must also arrive for Centro Americano identities

and Sur Americano bodies, LIKE ME! We can’t leave these folks hanging and

expect that our alternative discourses naturally fit them or just plain old

exclude them; yet they will have to define the parameters of their own

philosophy—no one else should. It will be an in-depth and long project of race

and decolonization. It begins ,and should be encouraged—not stifled—by all of

us. In fact, it is beginning though with the heavy entrance of Central American

youth into the United States from the frontera. People are beginning to realize

that countries like Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras actually exist!  We as the mixed bodies of Latino parents now have an

obligation to set up new spaces and disrupt current categories that would seek

to label us. We must find the power to name ourselves and self-determine our

bodies. If we feel like we fit into a current discourse, then let’s disrupt

that shit! No one else should be doing this for us; not Chican@’s, not

Boriquas, ni los Dominicanos, or other “Latinos”, and especially not White

people. We must find a new means of existing and knowing—that we can do such a

thing and in no one else’s shadow—or we risk our own narratives, and in the process…ourselves.

We as the mixed bodies of Latino parents now have an

obligation to set up new spaces and disrupt current categories that would seek

to label us. We must find the power to name ourselves and self-determine our

bodies. If we feel like we fit into a current discourse, then let’s disrupt

that shit! No one else should be doing this for us; not Chican@’s, not

Boriquas, ni los Dominicanos, or other “Latinos”, and especially not White

people. We must find a new means of existing and knowing—that we can do such a

thing and in no one else’s shadow—or we risk our own narratives, and in the process…ourselves.Tino

Note: I apologize for not adding references. If you'd like to know them please email me at Tinouvu@gmail.com

I also feel that I did not explain enough about why we need a radical racial politics, why it's even necessary at all. Nor did I feel I provided a well enough application for Chicano to me. I hope you can forgive, but I just hashed it out and needed it out ASAP. One more thing, I want to acknowledge that my Honduran and Ecuadorean heritage have not disappeared. It's something I wish to search out better and understand more of. But I'd like to do this process with my son, and not by myself one day...

No comments:

Post a Comment